With droughts being the norm in Australia, safeguarding water supplies is a priority for Gold Coast Water.

Gold Coast Water is one of Australia’s larger water and wastewater service providers, located in the southeast corner of Queensland, in the second most populous city in the state (525,000 residents, plus millions of tourists annually), south of the capital of Brisbane. Established as a directorate of Gold Coast City Council in 1995, Gold Coast Water is “a commercialized arm of the Council, run almost like a mini-business,” says director Dick Went. “We have profit-and-loss statements, and we provide Council with a dividend.” It operates with some autonomy, with approximately 420 employees, and is responsible for managing four wastewater treatment plants and maintaining 3,200 kilometers of water mains and some 2,900 km of gravity sewer mains.

Historically, Australia has always experienced periods of droughts, some quite prolonged, so water sources have traditionally been valued and protected. After a particularly bad drought in the late 1990s, the Gold Coast came dangerously close to running out of water.

Went is proud of the resultant drought management strategy developed by the directorate called Gold Coast Water Future. It’s a 50-year plan for ensuring a sufficient water supply in an area that suffers from erratic rainfall patterns. The plan is a multifaceted approach in the form of a substantial capital works program that includes a major water conservation program (including consumer education), rainwater tanks, recycled water, pressure and leakage management, constructing a desalination plant, raising the Hinze Dam wall to increase capacity, constructing a connecting pipeline to the neighboring main supply in Brisbane, as well as other initiatives such as providing dual reticulation to homes in new residential estates.

“We’ve been recognized for it as being a groundbreaking concept,” says Went, “since no one has done it previously as extensively or as effectively as we have, to the point where the State has taken over a number of the projects and processes that we initiated. In the beginning of the process there was a lot of public participation; when you get people engaged and taking ownership, it makes delivering major infrastructure a more painless exercise. The community is part of the planning, and they’re interested in how it gets delivered.”

As the drought started to impact the whole South East Queensland region, the Queensland government, in a move to regionalize the bulk water supply to ensure that no municipality would run out of water during a drought, announced in May 2007 that it was taking over ownership of all dams and water treatment plants in June 2008. Since then it has been constructing pipelines that link up major storage dams and continued the projects Gold Coast Water had commenced, such as raising the Hinze Dam wall and increasing the scope of the original desalination program.

Went, who has worked for the utility since its inception, previously as a manager, has mixed feelings about what the State calls “South East Queensland Water Reform.” “Losing ownership and control of the dams and water treatment plants to the State means we can’t implement or complete much of the types of work as we’ve done in the past, for which we’ve received national and international recognition. Because of the vertical disaggregation, we don’t have the same level of control. We now only operate the water distribution systems and the collection, treatment and disposal systems for wastewater. Our parent council isn’t happy about giving up that ownership and control, but as servants of the people, we will accept the change and make it all work, and work well.”

As part of that reform, in 2010 the water component of Gold Coast and its two neighboring councils will separate from their parent councils and be merged into one company, with the councils being the shareholders of that company. This new entity will be responsible for the distribution and sale of drinking water, while managing wastewater, recycled water systems and treatment plants.

The directorate’s current capital works budget is around $175 million, which is considerably less than in previous years. Most major projects are undertaken through an alliance arrangement. “We had looked at various infrastructure delivery options and decided on the alliance methodology,” Went says, “which is a partnership with one or more private-sector firms, one usually being a process and design consultant firm, the other a construction firm. The alliance is set up as a partnership agreement rather than being a standard design and construct contract. It’s a whole series of things that are done collectively; we, in effect, pay the bills, and the work is done by the other partners. There are conditions attached, such as ‘pain share, gain share,’ whereby if the project comes in under budget then the profit is shared, but if it goes over budget the pain is shared.” That model has been successfully used in at least five of the utility’s major infrastructure projects, including new treatment plants and upgrades, and areas of water and wastewater augmentation, as well as new works. “That’s how we manage to deliver on our capital works program. It’s such a quick escalation, there’s no way you could build up a workforce and expertise to do it in-house.”

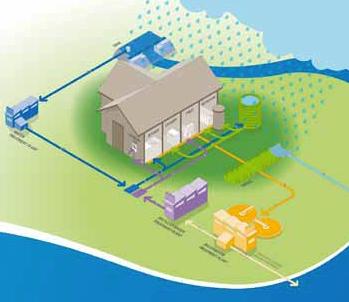

A critical WaterFuture project currently nearing completion is the Pimpama-Coomera area development within Gold Coast City. “It’s about the development of the equivalent to a small city from greenfield, using dual reticulation,” Went says. From December 2009, specially plumbed homes and businesses within the Pimpama-Coomera region will be supplied with both drinking water and Class A+ recycled water via two separate pipe networks. This supply arrangement is known as dual reticulation and will provide households with recycled water for toilets and outside irrigation use. “In addition, mandatory rainwater tanks are connected to homes to provide water for laundries, and the traditional primary water connection is provided for drinking, cooking and bathing. Using rainwater and recycled water in this manner can achieve savings in usage of fully treated drinking water of about 80 percent.”

Went notes that damming rivers is always a possibility to help ensure a reliable source of water, “but some people don’t like dams being built because it harms the environment, and they may argue for desalination, which is very expensive to build and operate, energy intensive and expensive. So there are arguments going back and forth; some are practical, others are financial, still others are emotional. It’s an interesting time for us, and we’re currently in the throes of setting up a $3 billion [in assets] company, starting from scratch, in an 18-month period. There’s a lot of activity going on here.”