Stand on the departures level of a new terminal, or in the atrium of a major hospital, and the engineering story usually points your eyes up to the roof. But for project directors and CFOs, one of the most important decisions sits under their feet: the floor slab.

Floor plates are often the single largest consumer of concrete in a building, and a major contributor to embodied carbon, foundation size and overall height. That’s why a family of “voided biaxial slab” systems – led by BubbleDeck and similar technologies – is moving from niche curiosity to serious line item in infrastructure capex plans.

At its heart, the idea is disarmingly simple:

if the middle of a concrete slab carries very little load, why are we still paying to pour it?

The structural trick: remove weight, keep performance

In a conventional flat slab, the top of the concrete takes compression, the bottom reinforcement takes tension, and a thick band of concrete in the middle mostly comes along for the ride as dead weight.

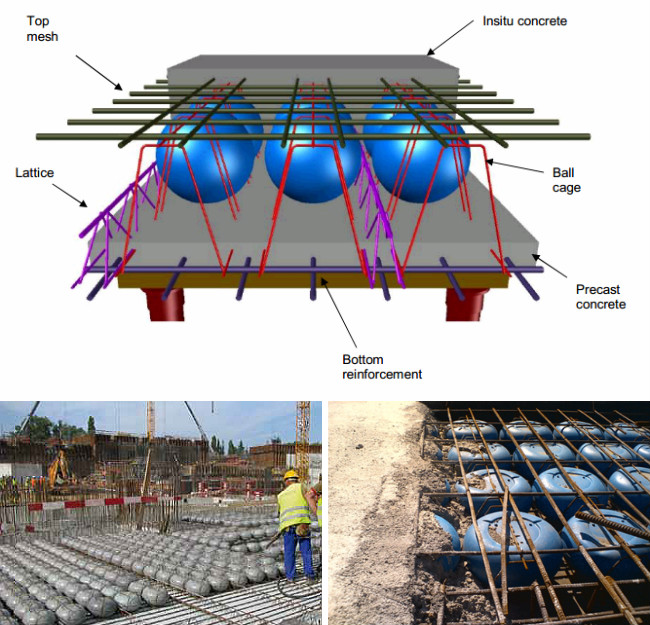

Voided slab systems surgically target that middle zone. Hollow plastic spheres or boxes – typically made from recycled polymers – are locked between top and bottom reinforcement mats. Concrete is cast around them to form a monolithic, two-way spanning slab.

From a distance, it behaves much like a solid flat slab:

-

Two-way action over a regular grid of columns or walls

-

Flat soffit – no downstand beams

-

Familiar detailing at supports and openings

But inside, a large portion of the non-working concrete is simply gone. Depending on geometry, that can mean roughly a third less concrete in the slab, which cascades into lighter columns, smaller foundations and, in some cases, the ability to shave a storey from the overall height while keeping the same usable headroom.

As one structural director at a global design firm puts it:

“We’re not selling bubbles. We’re selling a lighter, more efficient floor plate that gives the architect spans, gives the owner carbon savings, and gives the contractor a predictable cycle.”

How it’s actually built

For contractors, voided floors come in two main delivery models:

-

Precast “bubble panels”

Thin precast units arrive with bottom reinforcement, the voids and a thin concrete skin already assembled in the factory. These are craned into place, propped, stitched together with in-situ reinforcement and topped with a final concrete pour to create a continuous slab. -

Cast-in-situ modules

Alternatively, cages of voids and reinforcement are laid directly on formwork, topped with steel and cast in one or two stages. This suits markets where precast capacity is limited but site labour is more available.

In both cases, the underside is flat. That matters for:

-

MEP coordination: ducts, cable trays and pipework run under a smooth soffit without having to navigate beams.

-

Programme: fewer formwork steps and simpler geometry, especially in repetitive grids like car parks and terminals.

-

Architectural freedom: clean ceilings in public spaces and concourses.

Where the value shows up on real projects

The technology is now in service across a spectrum of infrastructure-adjacent buildings. Three application types illustrate where it earns its keep.

1. Airports and structured parking

Multi-storey car parks are almost a textbook case for voided slabs: long repetitive spans, high dead load and a strong incentive to minimise ramp lengths and overall height.

On a recent airport parking project, the design team adopted voided slabs over a conventional solid flat slab. The move delivered three tangible outcomes:

-

Spans in the 8–9 m range with a flat, relatively shallow slab

-

Reduced foundation demand on difficult ground

-

The ability to maintain clear height requirements for SUVs and vans without adding another storey

“From the airport’s perspective, we freed up just enough depth to avoid an extra level,” the project’s lead architect notes. “That’s real money in both concrete and façade, before we even start counting carbon.”

2. Hospitals and high-spec healthcare

Hospitals combine heavy services, strict vibration criteria and a requirement for future flexibility. In several European healthcare schemes, voided slabs have been used to create large, column-free diagnostic floors where long spans carry imaging suites, operating theatres and plant.

Here, the benefits are less about parking-style repetition and more about performance:

-

High stiffness-to-weight ratio for sensitive equipment

-

Flat soffits for dense MEP runs

-

Ability to reconfigure wards and treatment spaces over the building’s life

A capital projects director for a university hospital sums it up succinctly:

“We bought ourselves cleaner ceilings, quieter floors and fewer surprises below ground. The voided slab was the enabler, not the headline.”

3. Civic offices and public buildings

Municipal offices, libraries and cultural buildings are also turning to voided slabs, often as part of a broader sustainability agenda. The lighter frame supports:

-

Smaller foundations in constrained urban sites

-

Longer-term adaptability as departments grow, shrink or move

-

A meaningful reduction in embodied carbon that can be counted towards certification targets

For cities chasing both climate commitments and fiscal discipline, using less material in the most repetitive structural element of the building is an increasingly attractive proposition.

The delivery ecosystem: who actually makes this work?

Behind the clean diagrams, voided slabs create a distinct ecosystem of partners:

-

Void-former and system providers – licensing the technology, supplying design manuals, detailing rules and proprietary formers.

-

Precast manufacturers – producing bubble panels or semi-precast units under controlled conditions.

-

Reinforcement and ready-mix suppliers – adapting cut-and-bend schedules and mix designs for lighter, sometimes more heavily reinforced slabs.

-

Main contractors – revising temporary works, pour sequences and QA processes.

-

Consultants and checkers – providing the independent verification that asset owners increasingly expect for non-standard systems.

For suppliers, this creates a space that is less about commodity tonnes and more about engineering-led partnerships. Those who can bring detailing know-how, production consistency and on-site support stand to win repeat business as adoption grows.

Risk, governance and the Eindhoven lesson

No discussion of voided slabs is complete without acknowledging the 2017 partial collapse of a car park at Eindhoven Airport, which used a BubbleDeck-type system. The failure was linked to insufficient shear capacity at the interface between precast elements and in-situ topping, amplified by construction conditions.

The key lessons for asset owners are governance ones, not reasons to reject the technology outright:

-

Treat voided slabs as a specialist system

Ensure your contracts make clear who owns the design and detailing responsibility, including interfaces between precast and in-situ works. -

Insist on experience and independent checks

Ask for evidence of similar projects, and mandate independent review by engineers familiar with biaxial slabs and local codes. -

Keep voids out of high-shear zones

Around columns, walls and cores, slabs should typically be solid, with appropriate shear reinforcement and, where needed, shear heads.

Handled properly, voided slabs sit in the same category as post-tensioned floors or composite decks: proven, but requiring deliberate governance.

What C-suite leaders should be asking

For BE’s readership, the question is not “Is this clever?” but “When does this move the needle on my project?” A few filters help:

-

Do we have repetitive long spans?

Car parks, terminals, wards, teaching floors, concourses and office plates are prime candidates. -

Is weight or depth constraining us?

Poor ground, seismic demand, tight planning envelopes or height caps all increase the value of a lighter, shallower structural solution. -

How does this support our carbon and ESG story?

Voided slabs offer one of the few ways to make a step change in embodied carbon on a big, repeatable part of the frame without exotic materials. -

Is there a capable ecosystem in our market?

The presence of experienced designers, precasters and contractors materially de-risks adoption.

Looking ahead: digital tools and decarbonisation

As digital engineering matures, the case for voided slabs is likely to strengthen. Parametric tools can now optimise void layouts, reinforcement and thickness for each bay, negotiating between deflection, vibration, carbon and cost. Coupled with increasingly granular embodied carbon reporting, the ability to “design out” non-working material becomes both measurable and reportable to boards and investors.

At the same time, regulatory and investor pressure on embodied carbon is rising. For owners of airports, hospitals, campuses and civic estates, systems that remove a third of the concrete from one of the most repetitive elements in the building will not stay on the margins for long.

Voided slabs will never be as photogenic as a new bridge or terminal roof. But in a world where lighter, leaner, lower-carbon assets are no longer a “nice to have,” carving air into the flattest part of the building might prove to be one of the quieter revolutions in modern infrastructure.