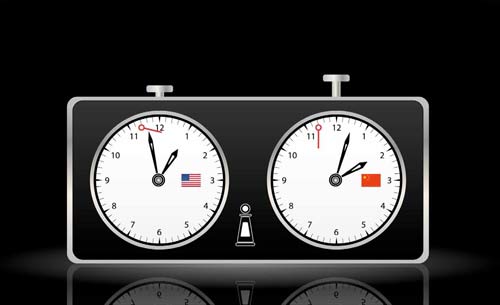

The Canadian government’s recent approval of China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) bid to buy Nexen, Inc. set oil and gas insiders abuzz: is it another smart strategic move in China’s massive chess game to ensure adequate and stable energy supplies for its ever-growing needs, or a calculated effort to gain entry to the North American, and more worrisome, the US energy patch?

North America has seen more than $17 billion in gas deals with Chinese companies since 2010, making it a top target for Chinese investment, but North America is by no means alone in enjoying attention from China.

China’s needs outpace domestic supply

China is now the world's largest consumer of energy. Though China is the world’s fifth largest oil producer, the country has been a net oil importer since 1993. The International Energy Agency estimates that China could become the world's largest consumer of oil, and its need for natural gas has been growing quickly as the country seeks to lower carbon emissions and aims for natural gas to reach 18 percent of the population by 2015.

Wary of unreliable supplies from the volatile Middle East and of Russia’s manipulative nature, Chinese companies have been busy using their state-backed might to strike partnership deals and make investments in nearby regions. These agreements have enabled China to set up networks that provide access to oil and gas supplies and pipelines, as well as technology and know-how to access their own reserves. Eschewing Russian and Iranian export corridors, for example, China now has pipeline access via Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.

China has been ramping up its partnerships and investments in other regions for a long time, with its first oil loan to Angola in 2004 for energy, infrastructure, and other projects. It has made loans to companies in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Venezuela to secure long-term oil and gas supplies, and joined into partnerships with companies in Australia, Africa, Russia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Canada and the US. In all, China has established 60 bilateral agreements with various countries, and cooperated with 40 countries in oil exploration and development projects.

“Playing nice,” so far

The CNOOC-Nexen deal is not China’s first foray into North America. In 2005, CNOOC bought 16 percent of MEG Energy, Ltd. to help develop an oil sands project in northern Alberta; Sinopec, China Investment Corp. and PetroChina have also made deals with Canadian companies; CNOOC provided development funding for some of Statoil ASA’s Gulf of Mexico leases and invested in Oklahoma’s Chesapeake Energy for stakes in several US fields.

So far, China has “played nice” as it has expanded its investments into other countries. The Chesapeake deal, for example, was structured so that CNOOC did not get an ownership stake and had no control over production. Whereas most deals include secondment (temporary assignment of the partner’s employees), the US deals have specifically excluded this to avoid potential political backlash. Adopting a more collaborative approach, China has forged alliances to gain advantageous opportunities but has not exerted its considerable political powers.

And the US has been a supportive ally, helping China reinforce its sovereignty by expanding its domestic gas production and increasing pipeline capacity. In exchange for access to the deep pockets of China’s state-owned energy companies, US companies have shared new technologies and methods for extracting unconventional resources. Houston-based Baker Hughes, Inc., for example, drilled China’s first horizontal shale oil well last year.

Inaccessible resources

Industry experts believe China holds the world’s largest shale gas reserves, with total recoverable shale gas resources estimated at 1,275 trillion cubic feet—more than all of the recoverable resources in the US and Canada combined—but those reserves are mostly beyond reach due to difficult geology, poor infrastructure, and water shortages.

China’s geology poses technological problems unique to the shale gas industry, with most reserves fully twice as deep as those in the US and further hampered by hilly terrain. While the government is seeking foreign investors with the technical know-how to exploit its reserves, China’s unique geology means that shale drilling technologies from other countries cannot be copied directly. Chinese companies are seeking to learn from their foreign partners, but deals that give them access to foreign supplies are critical.

China is also hobbled by a lack of proper infrastructure. Its fragmented pipeline network, processing and storage facilities are not currently capable of handling the potential volume promised by its reserves. As much of China’s natural gas reserves lie far below mountainous terrain, developing technology for the deep reserves isn’t the only obstacle. Typically, oil companies must construct new roads, bridges, and other infrastructure for large-scale drilling operations.

Water is another obstacle for China. In February of this year, China issued a warning about its worsening water problems. The government has issued strict water consumption restrictions and has heavily invested in water conservation systems, but these measures have done little to curb growing demand for water in the world’s second-largest economy. China’s water shortage issues could impact its ability to reach shale reserves using the fracturing methods that require large quantities of water. This, again, is where China’s partnerships and investments in foreign energy companies could eventually pay off in the form of development of alternative fracking components, like carbon dioxide and nitrogen.

Despite the challenges, China has designated shale gas as an independent resource, clearing the way for smaller companies, domestic and possibly foreign, to develop it. In December of 2012, the Deputy Director of the National Energy Administration reiterated that China is actively encouraging foreign companies to invest in exploration and development of China’s energy resources, and invites energy companies to set up research and development centers in China.

Is Chinese investment a real worry?

News of the CNOOC-Nexen deal has generated some concern over China’s potential undisclosed motives for gaining further inroads to the North American market. Though China has been playing nice thus far, some worry that this is just another move in China’s end-game of securing world dominance via control of not only economic but also energy markets. Part of the problem is the fact that Chinese oil companies are not privately owned; they operate with the backing of the Chinese state. The CNOOC-Nexen deal raises issues of American energy security, as it gives unprecedented influence over American reserves to a foreign government. China and other countries with state-owned oil and gas companies have in the past used their oil and gas resources for political leverage, so the worry is not unwarranted.

Aside from the aforementioned trade-offs for China, another deterrent to Chinese interference in the American oil and gas market should arise from the US’s six-decade commitment to protecting China’s imports in the South China Sea, using the US Navy to ensure safe passage. China’s confidence in that commitment, however, has appeared to waver in recent years as Washington has rebuked China’s conflicts with Taiwan and North Korea.

Regardless of uncertainty over China’s ultimate motives, it doesn’t appear that China will be slowing its foreign deal-making any time soon. Deal by deal and investment by investment, the world will watch as China’s energy chess game—and end game—plays out.

* * *