To keep up with South Africa’s rapidly growing demand for electricity, and a distribution system in need of modernisation, state-owned utility company Eskom is undertaking a massive construction and development programme.

Demand for power in South Africa has been growing rapidly for some years, finally outstripping capacity in 2008, with blackouts all too common around the country. Power generation and distribution company Eskom, established in 1923, has been pulling out all the stops to increase its power generation capacity and to improve the nation’s distribution infrastructure to keep up with this demand.

Phase one of the programme includes the construction of three new power stations, the first of which has been named Medupi, which means ‘rain that soaks parched lands, giving economic relief’. It will be Eskom’s first new coal-fired power station in 20 years, the fourth largest coal plant in the world and the largest dry-cooled power station ever built. Costing some R125.5 billion, Medupi will incorporate the very latest technologies. Its supercritical boilers will operate at higher temperatures and pressures than traditional boilers. “This will give us significantly higher efficiencies,” explains project manager Roman Crookes. “And by burning less coal per megawatt, we will also be emitting less CO2 and other gases into the atmosphere.”

The site for this prestigious project was carefully chosen. Thorough screening and feasibility studies of a number of sites identified a former farm at Lephalale, Limpopo Province, close to the border with Botswana, as the most suitable location. A range of criteria were assessed, including the availability of primary resources, the ability to connect to the Eskom grid, environmental acceptability and cost of production. Lephalale benefits by being just a few kilometres from the Exxaro coal mine and close to the existing Matimba power station, which already has access to the grid.

The licence to build was granted in 2006 and construction commenced in May 2007. The first of the six units of the power plant is scheduled for commissioning during the first half of 2012 and the remaining five units will follow at six- to eight-month intervals. Once fully commissioned, the plant will contribute 4,764 megawatts to the grid and is expected to have an operational life span of at least 50 years.

The second new coal-fired power station, Kusile, is now under way at Delmas, Mpumalanga Province, close to the existing Kendal power station. Kusile will have a prodigious appetite for fuel and is projected to consume 17 million tons over its 47 year lifetime. To supply this demand, Eskom has reached an agreement with Anglo Coal South Africa for the coal to be supplied through Anglo's empowerment subsidiary, Anglo Inyosi Coal. The first coal supplies are scheduled to be delivered in 2013 ahead of the commercial operation of the first unit in 2014, to allow the creation of on-site stockpiles. One of the greenest and most efficient aspects of the entire project is the ability to deliver the bulk of the 17 million tons by conveyors direct to the power station. This will save an unnecessary burden being placed on the province’s stressed road network.

Kusile is being built on a huge greenfield site covering 5,200 hectares of what was once farmland located between the N4 and N12 freeways not far from the existing Kendal station.

Kusile will be the first power station in South Africa to be fitted with flue gas desulphurisation, which is designed to remove oxides of sulphur (SOx) from the exhaust flue gases. This state-of-the-art emission reduction technology consists of a totally integrated chemical plant that uses limestone as feedstock and produces gypsum—an ingredient used in the manufacture of dry walls and ceilings—as a by-product.

Nobody is more attuned to the scale and importance of the project than Abram Masango, executive project manager of the Kusile Power Station Project. “Kusile is unique, not just in terms of its size but because it is incorporating some of the most advanced technology available. This means it will not just be an immensely impressive plant in terms of its extent and technology, but one of the most operationally efficient and environmentally responsible too.”

The construction phase has already presented some problems that have had to be overcome, says Masango. “One of the technical challenges we have met relates to the geo-technical conditions that exist across this extensive site. Building six units is not just a matter of doing the same thing six times: for example, on unit one we needed to install piles, but only unit six will reproduce that method for supporting the unit.” Units two to five will use a different technical solution involving shallow foundations.”

The first 800 MW unit is planned to start commercial operation in December 2014; thereafter, the second unit will follow in 12 months with units three through six following at eight month intervals. When fully up and running, the power station will have an installed nominal capacity of 4,800 megawatts of base load power.

Considering that South Africa is floating on a bed of coal, it’s not surprising that the vast majority of the country’s electricity is derived from that source. Wherever minable amounts of coal have been found, an Eskom power station will be nearby. Coal fired power stations represent 87 per cent of Eskom’s current capacity, and nuclear power contributes a further 5.5 per cent, which leaves the balance made up of a collection of other options such as hydro, wind and pumped storage. At this stage, Eskom has found no role for solar, although tests continue and some pre-feasibility studies are being planned.

The alternative option of choice for Eskom is pumped storage. At just a smidge over one per cent of annual energy production, the absolute contribution to the grid from the two existing installations is small, but it is valuable by virtue of its ability to fill in during peak periods. And when the third power station to be constructed in this phase of development, known as Ingula, is complete, this contribution will be upped by a further percentage point.

The Ingula pumped storage scheme consists of two dams with the capacity to carry 22 million cubic metres of water each. The dams are 6.6 kilometres apart, one located higher than the other, and the two will be linked by four underground waterways running through an underground powerhouse that will be fitted out with four pump turbines.

The idea is that when demand for power peaks and exceeds the base load supply, water can be released from the upper dam through the turbines to the lower dam, generating electricity. Then when demand is low, the turbines are used to pump the water from the lower dam back up to the upper dam—essentially storing energy for future use.

A pumped storage system is a ‘hybrid hydro’ scheme which relies on water head differential. In other words, water under gravity flows downwards to a turbine and generates electricity much as any other hydro scheme would do. The difference is, though, that instead of using the water once, it is recycled time and again by pumping it back to the upper storage dam. Within 10 minutes of a peak in demand, a power station such as Ingula can be pushing electricity into the grid.

“Coal, and to a lesser extent nuclear,” explains Avin Maharaj, project manager for the Ingula pumped storage plant, “provide the base load for the country’s needs. But twice a day, while the country wakes up or then settles down for the evening, demand shoots up. This means of generation is ideally suited to meeting short term demand.”

The head reservoir, called the Bedford Dam, lies on the Vaal River system in the Free State and the lower reservoir, called the Braamhoek Dam, is on the uThukela River system, 468 metres below in KwaZulu Natal. Between them is a series of tunnels varying in diameter from five metres to nine metres, depending on the exact role the tunnel has to play. From the Bedford Dam reservoir, water will travel two kilometres at up to eight metres per second down the two headrace tunnels which branch and reduce in diameter in order to power the four 333MW turbines.

Construction of the infrastructure began in January 2007, while the main underground work began in September 2008. The power station should come on line in 2013, with one unit being commissioned each quarter of that year.

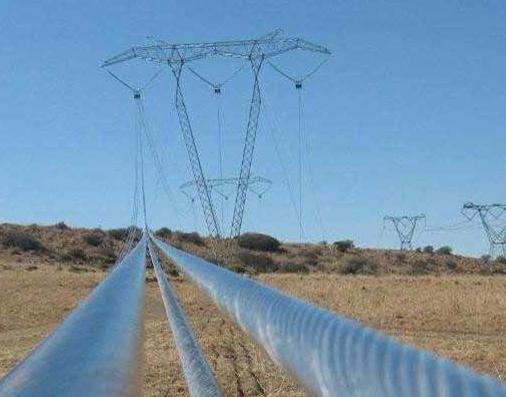

An extensive programme to improve South Africa’s transmission line network has also been underway for the past few years, under the control of Eskom’s Power Delivery Projects department which is entrusted with a massive budget stretching to tens of billions of rand. PDP is currently working on 22 projects and schemes, all in different phases of development and execution, on 51 sites around the country.

PDP was established in 2005 and is divided into four portfolios—three based on geographical coverage: Northern, Central and Cape, and the fourth responsible for the new 765kV integration. This includes the integration of the new power stations into the national grid. Power transmission is the movement of electricity from the point of generation to a substation from which it can be distributed to consumers, so PDP builds new lines and substations and refurbishes others; it also has the task of building the popular 765kV transmission network which will benefit the transfer of power from Mpumalanga down to the Western Cape.

Acting general manager for PDP Johan Bornman explains: “Normally, long distance transmission networks operate at 275 or 400kV but the further you go, the greater the loss of power. By increasing the potential of the transmission line to 765kV, the network operates more efficiently. It’s an expensive exercise because everything needs to be built on a much larger scale and it’s the sort of solution only justified where particularly long distances are involved or where a huge quantity of energy needs to be transmitted. To the best of our knowledge, we are one of only seven countries in the world that utilises the 765kV platform extensively.”

It is important to note that Eskom does not construct the line itself but carries out detailed design and procurement and management functions. In order to save costs, Eskom procures all its conductor, hardware and insulators to be used by the various contractors. “Our role is to design, procure and manage,” Bornman says. “In line with our contracting strategy, we put together a complete bill of quantities and a construction package that specifies all the necessary details for the construction tender. The actual supply and construction of the transmission line and substation work is left to specialist contractors.”

With much of the work on the 765kV lines being carried out at heights of 50 metres, there is a greater risk of accidents and injuries. Therefore great emphasis is placed on working with contractors to ensure that they carry out the proper procedures and supervision of work so that incidents are avoided. “At some point our LTIR ratio (lost time incident rate) was unacceptably high. We have a target of 0.4 and at its worst the figure hit 0.74. However, through hard work and partnerships with our contractors, the efforts we have put in are bearing fruit as the current figure is down to 0.3. This is testimony that safety is a priority in all our projects.”

Apart from focusing on making sure that new transmission lines and substations are built, PDP, together with its contractors, always gives back to the communities. A number of corporate social investment projects have benefited communities and improved the lives of local people. PDP constantly partners with contractors to identify needs in rural communities, with initiatives executed through the contractors. Bornman concludes: “This is part of the legacy to South Africa that our teams are delivering. These projects are in the interest of the country and we have the duty to execute them in a professional and safe manner, building Eskom’s image and reputation.”